Beyond Cities: Where short-term rentals actually happen

Posted on - December 22nd 2025

When we talk about short-term rentals (STR), the conversation almost always starts in cities: apartments in tourist hotspots, rising rents, housing pressure, regulatory crackdowns.

This framing is not wrong — but it is partial. It reflects where data, media attention, and political pressure have historically been concentrated. As a result, much of the STR debate has evolved around urban dynamics, while the broader territorial reality of the sector has remained largely invisible.

This matters, because how we frame STR shapes how it is regulated, managed, and integrated into destinations.

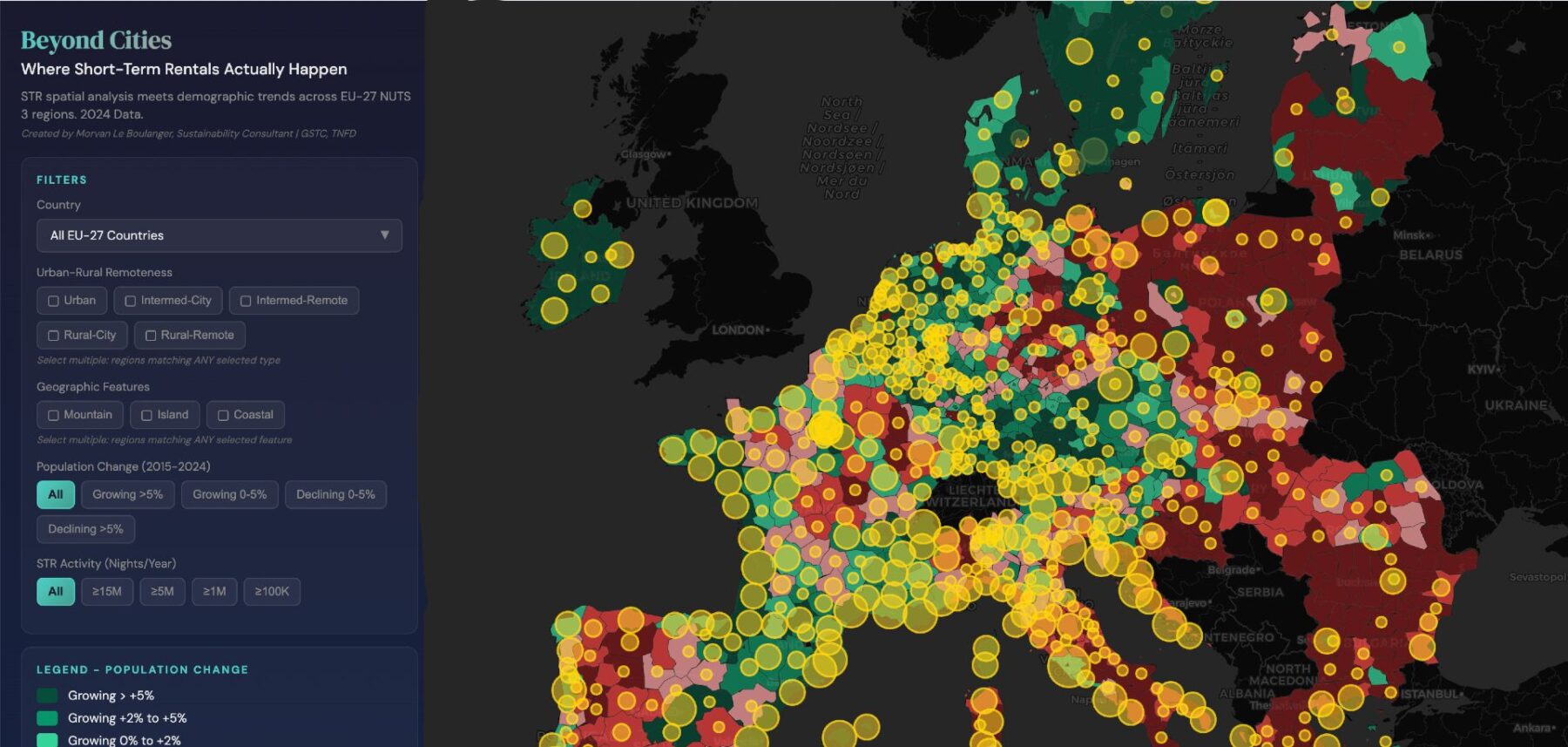

To explore this wider geography, I mapped STR activity across the EU-27 at NUTS-3 level, combining tourism intensity, demographic change, and territorial typologies. The resulting picture challenges some of the assumptions that continue to dominate public debate.

What the map shows

STR activity extends well beyond cities

One result stands out clearly at European scale: STR activity is not predominantly urban.

Across the EU-27, approximately 55% of STR nights occur outside predominantly urban regions. More than half of the market operates in intermediate, rural, coastal, and mountain territories — places where tourism is rarely framed as a housing disruption, but rather as a core economic function.

Yet the regulatory conversation continues to be shaped primarily by the remaining 45%, concentrated in major cities and metropolitan centres. This imbalance has consequences: policies designed for dense urban housing markets are often applied, by default, to very different territorial contexts.

Coastal and mountain regions are central to the STR economy

The map shows that coastal and mountain regions together account for a substantial share of STR activity across Europe. These territories are not marginal or niche markets — they form the structural backbone of the European STR economy.

At the same time, many of these regions face long-term economic and demographic constraints. Limited industrial diversification, seasonal employment, and outward migration have shaped their development trajectories for decades.

STR income, in this context, does not simply replace other accommodation types. It often complements declining traditional sectors and sustains local service economies that would otherwise struggle to remain viable.

Demographic decline and tourism intensity increasingly overlap

A more complex pattern emerges when STR activity is viewed alongside demographic change.

Since 2015, 232 NUTS-3 regions in the EU have lost more than 5% of their population, yet many of these same regions continue to host millions of STR nights each year.

Examples include:

- The Greek Cyclades (Mykonos, Santorini, Paros): –7.2% population, 5.5 million STR nights

- Croatia’s Primorje-Gorski Kotar: –8.4% population, 5.2 million STR nights

- Sicily’s Messina province: –6.7% population, 1.4 million STR nights

This coexistence of high tourism intensity and population decline does not imply that STR causes depopulation. In many cases, both dynamics reflect deeper structural transformations: aging populations, limited year-round employment, housing market rigidity, and changing regional economic roles.

What it does highlight, however, is a growing territorial tension.

The risk of museification

In several regions, tourism growth appears to coincide with the gradual erosion of permanent residential life. This phenomenon is often described as museification: territories that increasingly function as destinations for visitors while losing their role as living, year-round communities.

Museification is not an outcome of STR alone, nor is it inevitable. It is a risk that emerges when tourism development advances faster than housing, workforce, and community governance.

From a destination management perspective, these regions are simultaneously succeeding as tourism products and struggling as social systems. For the STR sector, this creates a paradox: the same dynamics that sustain short-term demand can undermine the long-term availability of workers, services, and local legitimacy.

What this means for destination management and STR operations

Much of the sustainability discussion around STR has focused on environmental performance — energy use, waste reduction, carbon footprints. These issues matter, but they are no longer sufficient to address the sector’s most pressing territorial challenges.

The spatial patterns revealed by the map point to three governance and operational priorities.

1. Workforce sustainability

In depopulating regions, workforce availability is becoming a structural constraint. Cleaning, maintenance, property management, and guest services depend on local labour markets that are shrinking and aging.

Seasonal staffing models that rely exclusively on remaining local populations are increasingly fragile. Workforce sustainability is therefore not only an operational concern for STR operators, but a destination-level challenge requiring year-round employment strategies, housing solutions for workers, and local training pipelines.

2. Economic resilience and seasonality

Many coastal and mountain destinations generate a large share of their income within a narrow seasonal window. While seasonality is often treated as inevitable, the data suggests it is also a governance choice.

STR operators, platforms, and destination managers have a shared interest in developing shoulder-season demand, diversifying visitor profiles, and stabilising income flows. Regions that depend on three or four peak months remain economically vulnerable — regardless of annual overnight volumes.

3. Community integration

In territories experiencing demographic decline, each remaining resident carries greater social and economic weight. STR operations that neglect neighbour relations, local hiring, or community contribution risk accelerating the very hollowing-out that threatens their own workforce and social licence.

Community integration is therefore less a reputational issue than an operational necessity. In fragile regions, long-term viability depends on alignment with local needs, not only visitor satisfaction.

Why this matters for the STR ecosystem

Public debate and regulation continue to frame STR primarily as an urban housing issue to be contained. This framing travels poorly to non-urban territories, where STR often functions as a development tool rather than a displacement mechanism.

Viewed through a territorial lens, STR contributes to:

- The spatial redistribution of tourism beyond capital cities

- Income generation in regions facing long-term demographic decline

- The maintenance of local services in areas where other economic activities have retreated

These contributions are not automatic, and they are not guaranteed. They depend on how STR is governed, integrated, and aligned with destination strategies.

A call to the STR ecosystem

The map and data are public. They invite a shift from one-size-fits-all debates toward territorially differentiated approaches.

For this shift to occur, the STR ecosystem — operators, platforms, destinations, associations, and policymakers — needs to engage on several fronts:

- Public–private data collaboration: Sharing occupancy, employment, and economic contribution data at regional level to improve evidence-based decision-making.

- Territorially differentiated representation: Moving beyond city-by-city advocacy toward coordinated positions that reflect non-urban realities.

- Long-term destination alignment: Embedding local hiring, off-season programming, and community contribution into STR operations by design, not by obligation.

- Shared responsibility for fragile territories: Acknowledging museification risks openly and addressing them collectively strengthens credibility and trust.

STR has the potential to sustain communities, support local economies, and contribute to territorial resilience across Europe. Realising this potential requires moving beyond defensive narratives and engaging seriously with the spatial realities the data reveals.

🗺️ Explore the Beyond Cities interactive map

How this analysis was built

This map combines Eurostat STR data at NUTS-3 level (EU-27) with Eurostat demographic change indicators and territorial typologies (urban, coastal, mountain, rural) to explore the spatial distribution of short-term rental (STR) activity across Europe.

Data sources: Eurostat (2024) tourism statistics for STR-related accommodation nights at NUTS-3 level; Eurostat population data for demographic evolution between 2015 and 2024.